Nerves 101 - Back to School

- Danielle Davey

- May 21, 2022

- 8 min read

Updated: May 20, 2023

Nerves are often overlooked in training and sometimes even in injury rehab. The ones connecting the nervous system that is, as opposed to one’s mental steadiness or courage! While nerves are often blamed for any pain that might look like “sciatica” and for numb patches of skin, nerves can actually play a part in a much greater variety of problems. Rather than an actual injury to a nerve, we more commonly see pole dancers and aerialists with symptoms of nerve “tension”. Some of these symptoms we might include:

Loss of grip strength or other weakness

A line of pull down a limb when going in to a stretch

Latent pain after stretching (an hour or so after)

Reduced range of motion in certain directions that doesn’t improve with stretching

Pins and needles or other strange sensations

… and more!

Before we start to look at what nerve “tension” is and how it might be affecting you, we need a little background on the nervous system as a whole.

Nervous System Basics

The nervous system is a mammoth topic, so let’s start with a simplified run down, in case you aren’t familiar.

Nerves run through our whole body, acting as its messenger service. They relay messages from the body to the brain or spinal cord and back again. While this sounds pretty simple, of course there is a lot that goes into making this system function like a well-oiled machine. Plus, a lot of messages need to be sent up and down for us to do even a simple pole spin.

The nervous system (NS) has two main sections: the central nervous system (CNS) and the peripheral nervous system (PNS). The CNS includes the brain and spinal cord. The PNS is basically all the rest!

Both sections of the nervous system are made up of cells called neurons. Neurons are a very unique kind of cell, as they are made to conduct electrical impulses. They even have insulation (myelin) like an electrical wire, to make sure the impulse, or message, makes it safely from one end to the other without being lost or mixed up.

The function of the CNS and PNS can be likened to a network of roads. Many small country roads carry vehicles (nerve impulses) to larger roads, until they connect in to a major highway (spinal cord) and finally reach a major city (the brain). In the brain, the message may visit a few locations to be processed. When it is decided what the message means and what the response needs to be, a new impulse or car is sent back out along the highway to the body part that needs to act.

Anatomically, the spinal cord divides itself out into nerve roots, which exit from the spine through small gaps between our vertebrae (neural foramina/foramen). As these nerve roots weave through the body, they join up with other nerves to make thicker nerve bundles, and split back off again closer to their destination.

Many of our nerve bundles have particular names. This helps us to understand their function and locate where any problems might be originating, as we will see later.

Our nerves both contain motor and sensory functions which help us to pole.

Key Divisions of the Nervous System and their Function

Dermatomes (Sensation)

“Derma” means skin. A dermatome describes an area of skin where your sensation comes from one particular nerve root. There is a dermatome for each of our spinal nerve roots (ie each nerve where it exits from the spine). There is a rough pattern that dermatomes usually take, though each person is slightly different. Matching any nerve like symptoms to a dermatome map can give clues as to (a) whether your symptoms might indeed be nerve related, and (b) where the problem might be coming from. We will discuss more later on.

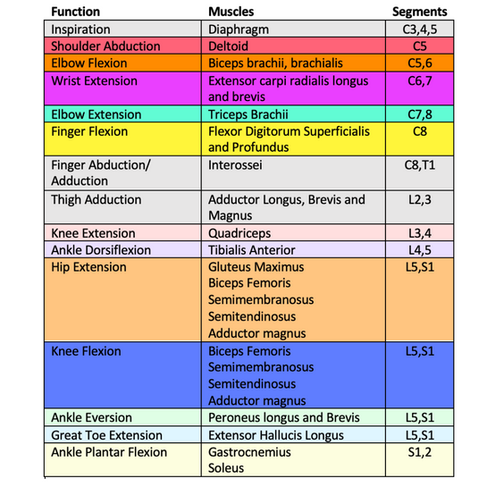

Myotomes (Motor Control)

“Myo” means muscle, so I bet you can now guess what these nerve divisions do! That’s right- a myotome is a muscle or group of muscles related to a particular nerve root. If your symptoms include muscle weakness that appears to be specific to a myotome, this can help your health care provider build a nerve-related diagnosis.

Peripheral nerve bundles

As mentioned above, once the nerves exit the spine, those spinal nerve roots don’t just keep to their own lane on the road. Those pathways mingle as they travel through the body. Some pathways merge for a time, splitting off again closer to their destination in the body. Where the nerves group together, the medical world has given some of these groups special names. You may have heard of some of them, like the sciatic nerve.

Some nerve symptoms can be traced to our nerve roots, using dermatomes and myotomes, while other symptoms don’t fit. These symptoms are may be coming from somewhere in a peripheral nerve bundle. The nerves can exit the spine totally fine, but become irritated further down, where they have joined to the sciatic or another nerve. In our blogs on upper and lower limb nerves, we will go in to more detail on this, talking about the most common nerve bundles we see giving people some pole struggles.

The Concept of Nerve “Tension”

Now that we have our nerve basics under our belt, let’s put this knowledge into a practice and understand how nerve tension works! Firstly it’s important to understand that a nerve does not have to be damaged to be causing problems. In fact our nerves are so robust that they are not often actually damaged!

Nerve tension is the term health care professionals used to use to describe limitations in mobility of the PNS. These days, I am not such a fan of this term. Tension implies that nerves get “tight” like muscles. This is actually impossible! Nerves cannot become tight, as they don’t contract or shorten, lengthen or stretch like muscles do. It also means if nerves are limiting our flexibility, we can’t simply stretch them out.

Nerve symptoms (other than actual damage) are usually a sign of one or more of:

Lack of ability of the nerve to move/glide through the body

Inflammation around a nerve

Irritability of a nerve as a result of upregulation of the whole nervous system (“fight or flight” response, aka sympathetic nervous system activation)

In the remainder of this blog we will explore each of these potential problems. Keep in mind that one often leads to another, so they are quite interconnected. If you want to know how these things might be impacting your poling, keep an eye out for our future blogs on upper and lower limb nerves!

How do nerves move?

Nerves are a bit like a power cord, as we discussed in this blog here (nerve vs muscle - what are we really stretching)! They slide and glide through the body - past, around and under other structures. What we used to think of as “nerve tension” is more lack of ability of the nerve to move normally.

Let’s dive in to the vacuum cleaner analogy. A vacuum has a long, coiled cord to allow you to move around the house while using it. The cord uncoils to allow you to reach further, but sometimes it gets caught on furniture. Since the cord doesn’t stretch, you become stuck. With nerves, we call this an anchor point. An anchor point in the body can be caused by any tissue that isn’t moving as it should be, like a tight muscle or stiff joint.

You’ll notice that even when your vacuum is stuck at an anchor point, electricity still flows and it still works. The cord, like a nerve, is robust, so it would take a fair incident to tear it or stop the flow of electricity entirely. You’ve probably heard of quite a few people tearing muscles or ligaments, but it is extremely rare to damage a nerve this way.

Having said that, there is a grey area where a nerve being stuck and compressed might stop sending signals quite as well. Then we might get changes in sensation such as numbness, tingling or pins and needles. We could also start to get some weakness if this compression goes on for longer or is more severe. Which nerve is compressed will determine the area the symptoms show up in. If the pressure on the nerve hasn’t been too long or severe, when we remove the pressure the nerve will function normally again.

What does a nerve “stretch” feel like?

If a nerve is anchored and stopping us from moving/stretching, we get a different response than if we were stretching a muscle (and not in a good way!) Symptoms of “stretching” or tensioning a nerve can include:

A thin line of pull down the area being stretched. The pull likely goes further than just the one muscle you’re trying to stretch, but may feel similar in intensity to a muscle stretch (i.e it doesn’t burn!).

Pins and needles or numbness, especially if holding the stretch for a while.

Flexibility seems stuck and won’t improve through the session.

Latent pain - pain coming on 1-3h after you finish stretching (different to delayed onset muscle soreness [DOMS], which comes on ~24h after working a muscle).

Inflammation around nerves

Other than mechanical pressure on a nerve, the function and mobility of a nerve can be affected by inflammation. This can happen in two main ways.

Inflammation can cause a chemical irritation to a nerve, making it sensitive and annoyed. Some of our nerves are designed to send messages to the brain to report on chemical inflammation. We can sometimes feel this as pain or itching.

At many points in the body, nerves are housed in protective casings called sheaths. These sheaths help guide the nerve through the body. If inflammation occurs within the sheath, there will be some swelling, which reduces space for the nerve to glide and things tend to get a bit sticky.

The “fight, flight or freeze” response and its role

Lastly, our nervous system can also be made more irritable by the sympathetic nervous system. You may have heard of this as our “fight, flight or freeze” response.

In short, if the body experiences any stress (mental, emotional, physical), the nervous system gears up to save us from threats. This is called nervous system upregulation and is one of many incredible ways in which our body attempts to protect us from injury. Fondly, we refer to this as getting ready to punch the lion (the stressor), run away or play dead and hope it leaves us alone.

When the nervous system is upregulated, it becomes more sensitive to pretty much anything and is on red-alert for danger! Something we normally cope with just fine, like temperature changes, rough textures, or end range stretching might now be interpreted as danger by the brain. This is why we are less flexy on days we are super stressed! It is also a good reason to take a minute or two to do some deep breathing, meditate or use another ritual to help you calm and focus the nervous system before any deep stretching. This includes flexy pole moves.

Phew! That’s a lot of information about nerves really fast! I hope this has given you all a bit more understanding of how your nerves work and a teaser on how they might affect your pole life. If you have any questions, hit us up on our socials through the week.

For specifics on what moves, positions and sensations you might get during pole and what to do about them, check back for our next nerve blog - Nerves of the Upper Body!

Are you experiencing nerve related pain? Or finding that you're not making progress with your flexibility?

Online telehealth appointments can be booked with the Pole Physio via our ‘Book Online’ page that can be found here. Assessment and tailored rehabilitation are provided in accordance with best practice and evidence-based treatment to help you unleash your 'poletential'.

Until next time, train safe.

The Pole Physio

x

Wakad Wagholi Viman Nagar Vishrantwadi Shivajinagar SB Road Ravet Pune best city Pimple Saudagar Pirangut Marunji Nigdi Pashan Pimpri Chinchwad Magarpatta Lohegaon Koregaon Park Kalyani Nagar Kharadi Pune city Service Pune Star Hotel Hinjewadi Pune desire Pune Airport city Akurdi Aundh Balewadi Baner Bavdhan Bhumkar Chowk Pune city Chakan Dehu Road Deccan Gymkhana Dhanori best city

Booking Cruise quality Gurgaon Escorts usually involves researching the agency's own credentials. Make sure that the Gurgaon Escorts Service you choose has robustly verified profiles of the Escorts and has a solid pricing structure. You want to minimize complications concerning your booking and your experience.